EMBARK Peer Coach Academy

Rod Rushing, Managing Director

Rod Rushing is a substance use disorder counselor and has also been on his own recovery journey since 2004. So, he has a unique amount of insight, and empathy, for the clients he works with and for the support he knows they need.

“As part of my recovery, I wanted to give back, so I worked with an agency that serves African Americans with HIV,” Rod said. “I offered them client advocacy, drove them to appointments, etc. And that made me realize the value of peer support, because they would talk to me about things they’d never talk to their providers about.”

Rod found himself disappointed in his own recovery journey from not getting the level of care he needed, to finding himself in support groups where he was the only gay man, or only white person in the group. “I didn’t see anyone that was like me, and it made me not want to open up and talk about what was going on in my recovery” he explained.

So, Rod set out to make things different for others and to make sure care reached a more diverse population. He worked for four years to become an addictions counselor, taking a job at Denver Health working in the HIV clinic. “I was having such a hard time getting my patients into substance use clinics,” Rod said. “I wondered why the barriers had to be so high. We ended up doing a project to streamline the facilitation of getting people into treatment. We were recognized for that work, and the methadone clinic offered me a job.”

Remembering what he had learned in his earlier days of his journey, Rod started a peer group. “I saw that engagement elevated immensely when peers co-facilitated support groups,” Rod said. “It was less about working on problems and more about checking in with someone and feeling connected.”

After three years, Rod traveled to Connecticut to become a peer coach trainer. “When I was a counselor, I saw that people were doing okay in treatment, but when they’d leave treatment they’d fall apart,” Rod said. “ I especially saw this with at-risk populations, such as the LGBTQ community, sex workers and others with other emotional baggage who often found connecting socially outside of counseling very traumatic.”

“I felt like there was a big deficit in available, thoughtful and generous support when they got out of treatment,” Rod said. “Now, I go to people who are in recovery and encourage them to become peer recovery coaches themselves.”

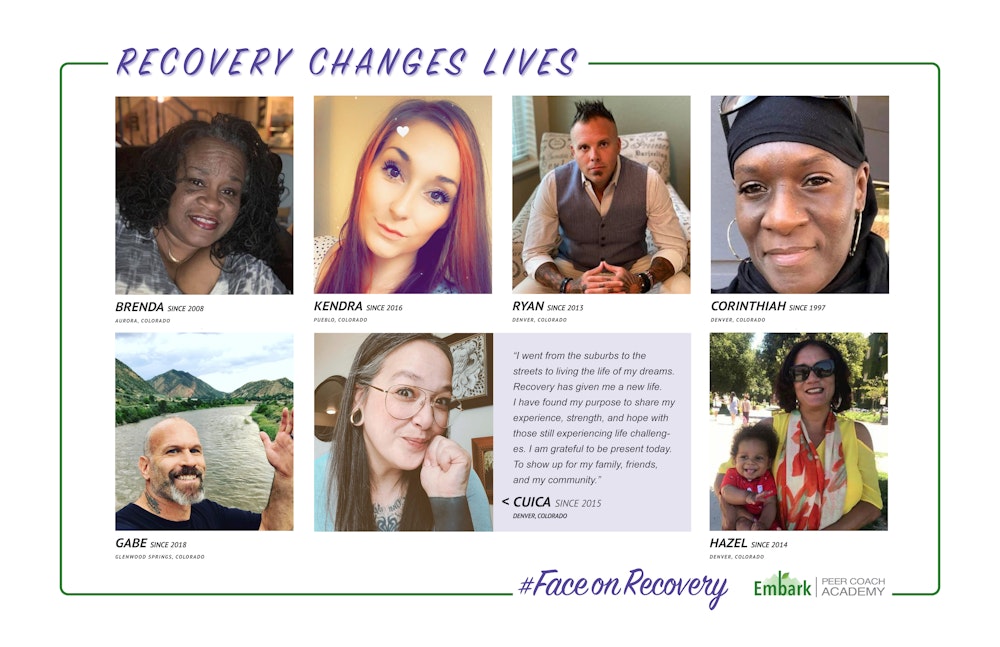

In 2015, Rod’s training group became the nonprofit Peer Coach Academy. Then in 2018, they started providing recovery coaching services and became Embark Peer Coaching Academy. They’ve now trained more than 1,600 coaches in Colorado and are in their second year of a grant for a program called Building Communities of Recovery, encouraging rural communities to develop recovery support and organizations.

Feeling at ease and getting the most out of counseling wasn’t just about seeing people you could relate to, Rod said. Language and cultural barriers can play a big role as well. He is currently working to include services in Spanish, and Embark has turned to working with Promotoras in the community. A Promotora is a member of the Hispanic or Latinx community who receives specialized training to provide basic health education in the community without being a professional health care worker. These are usually women and they are trusted by the women in their community. They provide a good entry for Embark to connect with more women of color.

“We now have seven virtual Spanish language Promotoras groups,” Rod said. “They are working in Glenwood Springs, Eagle and Mesa County as well as in the metro area. In addition, Embark collaborated with an organization in New Hampshire called Choices Recovery Coaching and created the first Spanish language translation for recovery coach training. The content has been donated to the National Latino Behavioral Health Association so that they can provide free training across the nation.

Embark opened their recovery center in early 2020 but had to close it in March due to the pandemic. So, Rod started a virtual clubhouse with 12 participating counties. The clubhouse offers free sessions including meditation, groups for cocaine or meth abuse, alcohol abuse, Women in Recovery, All Pathway Recovery and more. There are 60-70 meetings a week via the clubhouse, and people can look at a monthly calendar and decide what works best for them. “There are 7-10 meetings per day and it is a statewide resource, “ Rod said. “Although many people would prefer to meet in person, this has been a good way to connect with so many during COVID. We are all getting better about learning how to use telehealth, and it is helping us to reach a wider audience than ever before across the state.”

If I could talk to other providers I’d tell them:

Getting the person to feel safe is most important before we can talk about recovery. There is a lack of social support outside of clinical settings. While 13% of people launch well with the 12-step program, others have a more challenging journey. Their social skills were wrapped up in getting high, and they are scared to take chances in social settings while in recovery. They need a guide or mentor to take them to communities of recovery and help them find social bonds. We don’t send someone home with a cast on their leg without making sure they can get up their flights of stairs. But that’s what we do for those with substance use disorder.

I’d also tell providers that many people have added social and cultural trauma. Many in the LGBTQ community feel ashamed about who they are. Or women might have experienced domestic abuse in addition to substance use. Having someone that recognizes that or has the ability to engage with populations who have similar trauma can really be helpful.